Showing posts with label agile. Show all posts

Showing posts with label agile. Show all posts

Nov 23, 2015

Get Rid of Your Retrospective Meetings Once and for All

Agile Retrospective Meetings... Sounds boring, right?

And you're correct. They usually are. They don't give you the results you're looking for. Instead, they waste people's time and energy.

Jan 10, 2011

The Power of Low-Tech

This industry is obsessed with tools. Planning or tracking, the first impulse for any business is to reach for a software tool to handle their new agile project. While I can understand their reasoning, I think it's wrong to believe that a software tool is going to help achieve any agile goals.

I sometimes get asked to assess the software tools market and make recommendations on an agile tools mix for the best way forward. This implies that software tools are required for successful agile transformation. That is not true.

If your team is using Scrum, Kanban or XP correctly ("by the book"), you don't need to use any software tools. It's rather the opposite: Start out as simple as possible using nothing but pen, paper and some whiteboards.

This may sound a bit odd to some of you, so let me explain the reasoning below.

Dec 24, 2010

Dealing With Cowboys, Part II

The previous post on how to approach cowboy businesses concluded with:

The first step is talking to them about value-driven development, minimum marketable features and the importance of that throughout the entire development process. Explain why "business value" is the language they should be using when defining work items and not technical features. This is the easiest and most hands-on way to begin the transformation. It's also the only way customers and stakeholders can understand what the programmers are actually working on.

Stakeholders should handle the business, not the developers. That should be the focus when dealing with cowboys: wresting control back to the customer and help them slow down their frantic code herding. Pull in the reins if you will.

A quick recap: Cowboys have seized control over the process. This means a lot of time is spent doing stuff they think is most important and not necessarily what is most valuable for their customers. And here lies the key to success: get the organization back to being in a constant focus on providing customer value.

The first step is talking to them about value-driven development, minimum marketable features and the importance of that throughout the entire development process. Explain why "business value" is the language they should be using when defining work items and not technical features. This is the easiest and most hands-on way to begin the transformation. It's also the only way customers and stakeholders can understand what the programmers are actually working on.

Sep 29, 2010

Burn Up or Burn Down

Feedback is the number one factor when you are planning and managing your projects. In order to prioritize and add (or remove) tasks, you must know how the project is doing. For this you need data -- relevant and up to date. Gathering project status data is time consuming, boring and disruptive. So you need to strike a balance between how much info you want and what it costs to gather it.

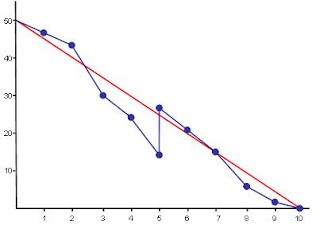

Speaking in agile terms, we are talking about an informative workspace where both the team and stakeholders should, at a glance, be able to ascertain current project status. One part of this puzzle is burn up and burn down charts. They are used for different purposes:

A burn down chart is used during the iteration and displays estimated work left to complete all tasks in the current iteration.

This chart answers the question: Is it possible to finish the current iteration on time? The x-axis is time (days) and the y-axis is estimated work left (hours or points).

Each day, the team gathers in front of the chart and adds a new point to it.

Blue points shows work left and red is the ideal. The team is finished when the blue line reaches zero. This example shows a two-week iteration.

A burn up chart is used to for long term planning (release planning) and shows how much work is completed. It is slightly more complex, but conveys a more information than its burn down friend. It answers question such as:

- Is our velocity stable over time?

- How much work is left before release?

- Are we removing or adding stuff to the backlog?

- What is the projected prognosis for completion?

It is also a great tool when performing post-project retrospectives and is an excellent communication tool to use as a status document for absent stakeholders.

Burn up charts displays iterations on the x-axis and accumulated story points in the y-axis. When the iteration is completed, you just sum up all completed stories (ie. your velocity) and plot it on the chart. In a perfect world, the result should give you a straight line (constant velocity).

The blue line shows total planned work and the red displays produced work for each iteration. Note the bump between iteration 5 and iteration 6. This shows that the red velocity was constant, but more work was added to the backlog (or estimation changed).

In summary:

- Use burn ups to see how much work has been completed and to plan and calculate releases over several iterations. I recommend using one-week iterations. If that is not possible, just plot each weeks work anyway. Completed story points is the measured unit here.

- Use burn downs if you need daily progress reporting and update the chart duringstand-up meetings. Risk for "micro management" here, so don't draw any conclusions to early! Use hours.

- You can use burn ups during the iteration as well.

Sep 21, 2010

Are there Leaders in Agile?

I recently had an interesting discussion about what part leaders play in an agile team. Specifically team leaders, CTO's and project managers. This is a part of this:

In my experience, the word leader instills a certain image about a strong "command and control" person, who manage people into doing stuff. Words such as authority, coordination, structure and timing springs to mind. A leader is generally highly committed to the work and feels personally responsible that the task gets completed. This of course is a heavy burden to carry, especially since the leader is not the person who personally works on the task. Instead, the leader is completely dependent on his team. This can often be frustrating and some side effects of this is that pressure is added or moved on to the developers, followed by the occasional flogging (if they slack) or partying (if they success).

You don't really need that in an agile setting.

In fact, having a person on the dev team who is supposed to be a leader may instead disrupt the teams work, since the other members looks to the leader for answers instead of themselves and thus negating the effect of any self organization. Also, implementation decisions should be solved by the team during their estimation effort. If any one person on the team is regarded as a leader, he or she may sway the balance and non-technical arguments may influence the design which could lead to bad implementation.

Another problem is the need to "look good" in front of your boss. This may result in completing tasks that the leader feels is important rather than what is most important for the business right now.

Contrary to this, agile teams are self-organized. Being self-organized means that the team members themselves sign up to the tasks they want to work on and decides how they are going to do it. When you choose what do to and truly commit to it, you feel empowered, energized and take a personal interest in getting the work done. The result is increased team motivation and a much higher chance of success.

I suggest that, instead of having one person act as a leader, you let the interaction between the customer (prioritize) and the team (estimate) do its thing, preferably using the planning game. For this to work, you need the courage to trust that the framework has everything it needs to solve any problems. Some calls it "the magic of collaboration" and when it works, it is extremly powerful.

Note that the role of agile coach is nothing like this. It may be a type of leader, but their primary goal is not to control, but rather to support the team being their "servant leader" carefully helping the team to grow their skills and learn to use their abilities as best as possible.

So in short, I cannot really see what a leader could do in an agile environment.

Related to this is the cool presentation about "The amazing truth about what motivates us" which I highly recommend:

In my experience, the word leader instills a certain image about a strong "command and control" person, who manage people into doing stuff. Words such as authority, coordination, structure and timing springs to mind. A leader is generally highly committed to the work and feels personally responsible that the task gets completed. This of course is a heavy burden to carry, especially since the leader is not the person who personally works on the task. Instead, the leader is completely dependent on his team. This can often be frustrating and some side effects of this is that pressure is added or moved on to the developers, followed by the occasional flogging (if they slack) or partying (if they success).

You don't really need that in an agile setting.

In fact, having a person on the dev team who is supposed to be a leader may instead disrupt the teams work, since the other members looks to the leader for answers instead of themselves and thus negating the effect of any self organization. Also, implementation decisions should be solved by the team during their estimation effort. If any one person on the team is regarded as a leader, he or she may sway the balance and non-technical arguments may influence the design which could lead to bad implementation.

Another problem is the need to "look good" in front of your boss. This may result in completing tasks that the leader feels is important rather than what is most important for the business right now.

Contrary to this, agile teams are self-organized. Being self-organized means that the team members themselves sign up to the tasks they want to work on and decides how they are going to do it. When you choose what do to and truly commit to it, you feel empowered, energized and take a personal interest in getting the work done. The result is increased team motivation and a much higher chance of success.

I suggest that, instead of having one person act as a leader, you let the interaction between the customer (prioritize) and the team (estimate) do its thing, preferably using the planning game. For this to work, you need the courage to trust that the framework has everything it needs to solve any problems. Some calls it "the magic of collaboration" and when it works, it is extremly powerful.

Note that the role of agile coach is nothing like this. It may be a type of leader, but their primary goal is not to control, but rather to support the team being their "servant leader" carefully helping the team to grow their skills and learn to use their abilities as best as possible.

So in short, I cannot really see what a leader could do in an agile environment.

Related to this is the cool presentation about "The amazing truth about what motivates us" which I highly recommend:

Aug 15, 2010

The big rewrite

I see it all the time and it goes like this:

Our system sucks. Let's rewrite it! Let's do it right this time!

With a fresh team, new technology and no legacy code, the team is left alone to hack away at the brand new version of the system, full of energy, enthusiasm and commitment. The organization gives their blessing with a perfect environment, great tools, great setting and complete trust.

As the story goes, each programmer now happily start coding their piece of the system. Relaxed, in the zone, that perfect place where code just seems to flows from the keyboard into the system. Perfect code -- your code. Earphones blazing away your favorite music, shielding you from any disturbance. Life is good.

As the story goes, each programmer now happily start coding their piece of the system. Relaxed, in the zone, that perfect place where code just seems to flows from the keyboard into the system. Perfect code -- your code. Earphones blazing away your favorite music, shielding you from any disturbance. Life is good.

This goes on for several months, maybe a year, but eventually the system is released. With a huff and a puff, the thing eventually is up and running! And it works! Rejoice, let's make some money! After all, that is why we say that software is valuable for our organization and that is the only reason we are getting paid to produce it. Working software is an asset. Management is happy, customers are happy and the team feels good. A job well done. Now they can relax.

During this honey moon, a few (well, quite a lot actually) bugs are found and fixed. Several important changes and new features are implemented. Things starts to heat up and it seems like this flow of new changes never ends. It is a steady stream of new features, mixed up with bugs. The team is running just a head of the tide, constantly adding new stuff to the system.

A bad smell

After a while, development seems to drop somewhat. The stream of changes is slowly catching up to the team. What used to take only a couple of hours to fix now takes several days, and for some reason a lot of time is spent fixing bugs which seems to pop up all the time. The team squash a bug, only to have it pop up in another, unrelated, part of the system. Even worse, the fix itself introduces another issue which must be fixed. Testing also takes longer and longer, since everything is done manually and every change results in a complete re-testing of the whole system. The testing guys are slowly drowning in tests, sometimes allowing things to slip just to make the next release on time. Meanwhile, the code grows more and more, attracting more bugs, more complexity and more todos.

Huh, what is going on here?

Baffled, management does not understand why things is going so slow all of a sudden. The same stuff the team did just a a few months ago now requires a huge effort to implement. Problem is, the world is still turning, competition is fierce, customers demanding and those features must be released now!

It is obvious that the team cannot handle this on their own anymore, so what is a manager to do? Step in and help the team of course! First they must know what is going on, so they add more meetings and daily status updates. "Where are we and much time left do we have?" "More detailed specifications!" "Why is this taking so long?" Lets apply some healthy pressure by assigning selected parts of the system to specific members of the team. That should make it clear who is responsible if anything goes wrong! Overtime is encouraged and rewarded. The message is crystal clear: failures are not accepted and no missteps allowed.

Morale starts dropping, overtime is the norm and there are signs of early burn outs. People are on their edge all the time, and some have problems controlling their frustrations. Team members blame each other and the lead programmer is often seen working late, fixing other team members code. No-one is willing to take any risks and creativity is stifled. Some have learned that to avoid the heat it is best to not do anything at all while still manage to look busy.

After a while, some team members quit and eventually the manager gets removed (or promoted) and new, fresh and eager people arrives to replace the old guys. After some time, it is clear to them what must be done about the system and they convince the organization:

Damn, this system sucks! Let's rebuild it!

And so on...

What happened?

It was clearly not an overnight thing. Instead, slowly, like a creeping bad feeling which got stronger and stronger and eventually the whole thing just fell apart. I am sure this happens all over in all types of organizations, and I am sure you have seen it yourself. Maybe not as extreme as this, but bad enough.

It was clearly not an overnight thing. Instead, slowly, like a creeping bad feeling which got stronger and stronger and eventually the whole thing just fell apart. I am sure this happens all over in all types of organizations, and I am sure you have seen it yourself. Maybe not as extreme as this, but bad enough.

In reality, the whole project was pretty much doomed from the beginning. All the signs were there, but no one was there to watch for them. I can not really blame management for what happened, it is not their job to be masters of systems development after all. The fault here is the developers. The organization put their trust in the programmers and they failed. I see this all the time: individual programmers working on their own, creating code that may work for the moment, but over time degrades into an unmanageable big ball of mud.

Then the blaming starts: it is either the customer or the organization (or both) which forced the code into this situation. Well, I don't believe that. Not for a second. It is our responsibility, our duty, to act as professionals and to do everything in our power to not let this happen. Yet it does. All the time.

Then the blaming starts: it is either the customer or the organization (or both) which forced the code into this situation. Well, I don't believe that. Not for a second. It is our responsibility, our duty, to act as professionals and to do everything in our power to not let this happen. Yet it does. All the time.

Programmers should be working together

The first step is to drop the age old pretense that hacking is an art done in isolation, in a hacking comfort zone. That mentality has to go. Next, we must start working together, not just sitting in the same room, but truly working together. Think of this as being part of a band if you want to. Everyone needs to be perfectly in sync with each other for the music to work. It is the same with developing software.

Creating truly great, sustainable software of todays standards requires that we work as professionals and that means working in teams. In my world that boils down to embracing agile values, and to teach our peers and managers how and why. It is not enough that we should blindly follow these values and practices. It is a good start, but the goal is to eventually create something new and unique with them. To bend the rules, to adapt and to make them our own.

The first step is to drop the age old pretense that hacking is an art done in isolation, in a hacking comfort zone. That mentality has to go. Next, we must start working together, not just sitting in the same room, but truly working together. Think of this as being part of a band if you want to. Everyone needs to be perfectly in sync with each other for the music to work. It is the same with developing software.

Creating truly great, sustainable software of todays standards requires that we work as professionals and that means working in teams. In my world that boils down to embracing agile values, and to teach our peers and managers how and why. It is not enough that we should blindly follow these values and practices. It is a good start, but the goal is to eventually create something new and unique with them. To bend the rules, to adapt and to make them our own.

In following posts, I will try to explain these values and how they can change the way we create valuable, working software.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)